Grains of Opportunity: Wheat Production and Trade in the Americas

As nascent bakers around the globe used their time in lockdown to hone their focaccia and sourdough skills, unassuming flour rose to claim a starring role in many kitchens. Of course, flour has always been a pantry staple, but retail demand for the product exploded in many parts of the world as folks stuck at home reconnected with their ovens. This phenomenon was particularly extreme in the United States, where flour manufacturers saw retail demand for their products grow by as much as 2000% while the country was in confinement.

Flour is most commonly made from milled wheat. Although alternative grains can also be used, today we are going to focus on wheat as a global agricultural commodity and its trade dynamics across the Americas. We actually first focused on wheat on this blog back in 2016, and if you’re interested in some additional background, that post would be a good place to start. But with all the attention foisted on wheat over the last few months, it is an opportune time for an updated look at this critical grain and its role in regional agricultural trade.

Amber Waves of Grain

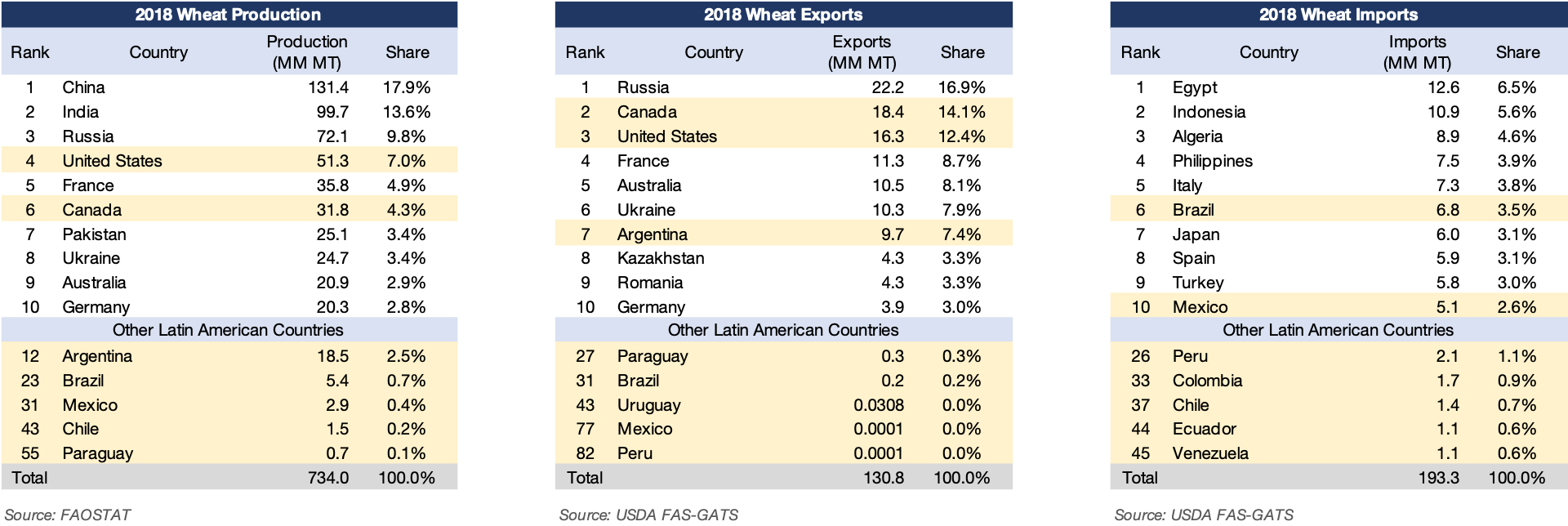

According to the FAO, most of global wheat production is concentrated in China, India, and Russia. In 2018, the collective production of these three countries accounted for 41.3% of the global harvest. But there are important producers in the Americas, as well. The most prominent of these are in North America. The United States produced 51.3 million metric tons of wheat during 2018, with Canada adding another 31.8 million tons to the global tally.

Within South America, wheat production generally takes a back seat to other crops. Only Argentina stakes its claim as a major producer. Argentina is the twelfth largest wheat producing country in the world, with an output of 18.5 million metric tons during the 2018/2019 production year.

Of course, production is only one piece of the puzzle. Through the vehicle of trade, wheat is moved around the region and the world to balance supply and demand. The United States, Canada, and Argentina all look to the export market to absorb production in excess of domestic demand. These three countries send thousands of metric tons of wheat each year abroad, both to their regional neighbors and destinations across oceans.

Even as wheat production is relatively limited in many parts of the Americas, demand for wheat products is not. As such, many countries in the region are key importers of wheat. Brazil and Mexico were among the top ten global importers of wheat in 2018. In that same year, other South American countries, including Peru, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, and Venezuela, all imported more than 1 million metric tons of wheat.

The Latin American Opportunity

Latin America is likely to offer an environment in which wheat demand will grow in the coming years. Albeit at slower rates than previously witnessed, regional populations will increase, and with them, the number of mouths clamoring for wheat products. Furthermore, as economically vulnerable populations seek to get the most caloric bang for their buck, wheat-based products will remain a popular source of nourishment.

The Covid-19 pandemic could accelerate this trend. Governments, particularly those of less stable nations, will be incentivized to keep the peace by providing their people with ‘bread and circus’. History has proven time and again that food security is of paramount importance and many governments will be keen to maintain stability by keeping cupboards and bellies full.

Generally speaking, consumers in Latin America view wheat products favorably. The specific products in which wheat is consumed vary from country to country, but each market offers some kind of wheat-based staple, ranging from flour tortillas in Mexico to medialunas in Argentina. Many of the trends which have been working against wheat consumption in more developed markets, for example a preference for gluten free products, are not yet present in force in the region. While these shifts may come in time, the current outlook for a growing demand in the region remains strong.

Even as the fundamentals are strong, suppliers will have to invest time and effort into understanding the needs of an individual market. Expending a little extra energy to grasp the idiosyncrasies of a specific market and connect with buyers will pay off in spades down the line.

Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

Regional suppliers are already well positioned to capitalize on the growing desire for wheat in Latin America. Logistical proximity along with well-defined trade routes and relationships, make the United States, Canada, and Argentina the logical choices for meeting wheat demand in Latin America. Furthermore, many favorable trade agreements provide these suppliers with privileged tariff treatment across the region.

Policy shifts are also increasing market access in parts of Latin America. Last year, Brazil, the region’s largest wheat importer, agreed to open a Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) of 750,000 metric tons. The TRQ had been part of Brazil’s obligations tied to its participation in the World Trade Organization, but it had never been enacted. Under the TRQ, up to 750,000 metric tons of wheat can be imported tariff free each year from countries with which Brazil does not have a preferential trade agreement. Imports above this amount will be levied with a 10% import tax.

The enactment of the TRQ was a win for suppliers from the United States and Canada, where producers are licking their lips to get access to this volume. Argentine producers already enjoy tariff free access to Brazil under Mercosur, the South American common market. However, given that Argentine producers are subject to an export tax of 12%, Argentine product will take a competitive hit when compared to product from North America. This dilemma highlights the critical role trade liberalization plays in capturing demand opportunities for agricultural products around the region.

Wheat suppliers across the Americas have a tremendous opportunity for growth. With supply limited to a few countries, but demand growing throughout the region, wheat producers in the Americas are uniquely positioned to address this need. Profiting from these opportunities, however, will require suppliers to invest in understanding these markets and building relationships with potential buyers. Simultaneously, they must push forward with initiatives and policy frameworks that streamline market access. The suppliers that pursue these goals most effectively will enjoy the richest harvest.

Flour may have risen to a central role in bakers’ lives over the last few months only to fall as more normal daily routines return. But even as our new baking hobby fades into the background, wheat will still be moving to and fro across the Americas, generating opportunities all along the agricultural supply chain.